Article 2 by Paul Kaman:

“The Evolution of Refueling: From Bertha’s Courage to Tomorrow’s Sky Stations”

Walking through EVS Saudi 2025 early this month, I found myself mesmerized by the sleek charging stations nestled between futuristic vehicles. These silent pillars of power stood in stark contrast to the roaring engines and oil-stained concrete that defined my childhood. And just like that lonely FlyNow eCopter I wrote about earlier, these charging stations whispered of another revolution in the making.

It got me thinking about those 1900-1913 Fifth Avenue photographs again—the ones showing that breathtaking thirteen-year transition from horses to automobiles. But this time, I wondered: where did all those early drivers get their fuel? What did the first gas stations look like? And what might their evolution tell us about the charging networks we’re building today?

Sometimes history hands us perfect poetry. Did you know the world’s first “fuel stop” wasn’t a station at all, but a small pharmacy in Wiesloch, Germany? I didn’t either until recently, and the story behind it stopped me in my tracks.

It begins with what might be history’s first automobile “theft.” The year was 1888, before automobiles were even a recognized concept. The “thief” was Bertha Benz, wife of Carl Benz, who had created a motorized vehicle but lacked the courage to demonstrate its potential. Some locals had already branded her a witch for her involvement with this strange contraption that moved without horses. The Church frowned on it, and the State forbade Carl’s contraption outside their property. Local police were stationed outside their front gate to prevent any of Benz’s mischief.

One August morning, without her husband’s knowledge or permission, Bertha took their automobile and, along with her two teenage sons as accomplices, embarked on a daring 66-mile journey from Mannheim to Pforzheim to visit her mother. She used a back exit out of the property and gave the front gatekeepers a slip. This wasn’t just a family visit—it was an audacious statement to the world.

I can almost picture it: Bertha at dawn, perhaps nervous but determined, her boys excited and scared in equal measure, as they pushed that primitive vehicle onto dirt roads meant for horses and carriages. The route was challenging, and the technology was untested for such a journey. Their wooden brake pads wore thin, prompting a stop at a shoemaker who added leather to improve stopping power—an impromptu innovation that would later become standard.

When they ran out of fuel, Bertha didn’t panic. She confidently pulled into the city pharmacy in Wiesloch and purchased ligroin, a petroleum solvent. This ordinary pharmacy, still standing today as a small museum, unknowingly became the world’s first refueling station—a humble beginning for what would become a global infrastructure.

From sunrise to sunset, they traveled, stopping at rivers and streams to collect water for the overheating engine. When they finally reached their destination, Bertha sent a telegram to her husband: Mission accomplished. In one bold day, she had proven what this invention could do, sparking the automotive revolution that would transform Fifth Avenue and the world beyond.

This story catches in my throat because it reminds me that revolutions aren’t just about technology—they’re about human courage, about seeing possibilities others miss, about taking risks when conventional wisdom says to wait. Bertha wasn’t an engineer or an industrialist (women in those days were not allowed higher education). She was simply someone who had uncommon sense and believed deeply that a better way was possible for everyone. More than wheels, she had balls.

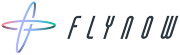

It would be nearly two decades after Bertha’s journey before the first purpose-built gas station appeared in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1905. Just a simple gravity-fed tank with a hose—nothing fancy. But it was revolutionary because it was dedicated solely to fueling automobiles. Someone had seen the future enough to invest in specialized infrastructure.

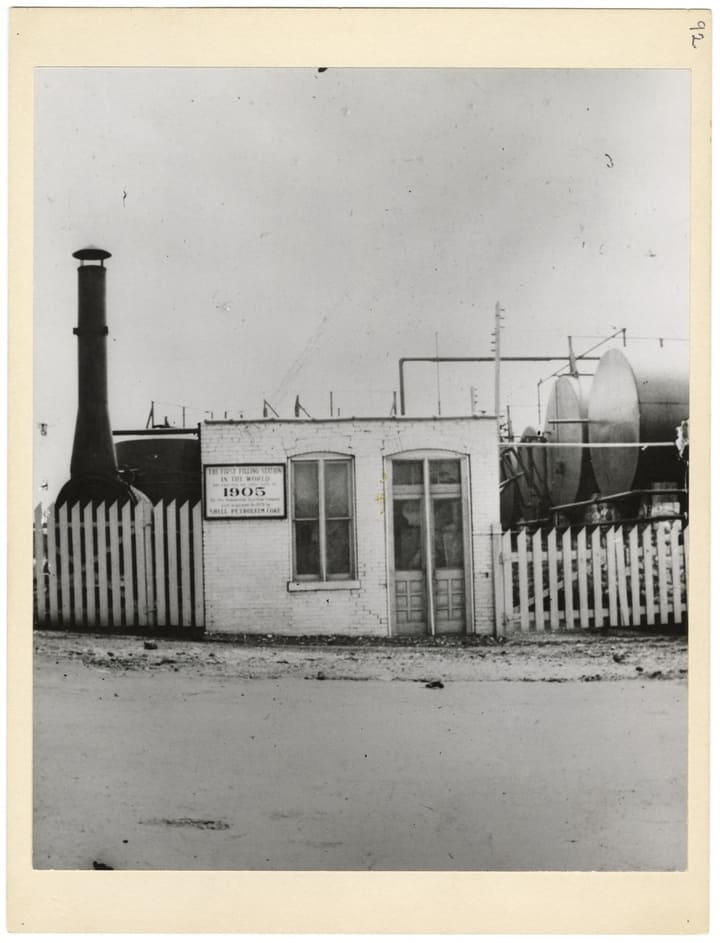

The real game-changer came in Pittsburgh in 1913—that pivotal year when horses were disappearing from Fifth Avenue. The Gulf Refining Company opened an architect-designed “drive-in” station with all the bells and whistles: a pagoda-style brick building, free air and water, crankcase service, tire installation, and even the first road maps. On its first day, it sold 30 gallons of gasoline at 27 cents per gallon. By Saturday, they’d pumped 350 gallons.

Think about that growth curve. From 30 to 350 gallons in less than a week. From one station to hundreds of thousands globally in just decades. From a side business at pharmacies and blacksmith shops to a specialized industry that reshaped our landscapes, our cities, and our daily lives.

Standing there at EVS Saudi 2025, watching people casually plug in vehicles that would have seemed like science fiction just years ago, I couldn’t help but wonder: Are we witnessing another 13-year miracle? Are today’s charging stations the equivalent of that first Gulf station in Pittsburgh? Will our children someday struggle to imagine a world where massive gas stations dominated every major intersection?

The parallels aren’t perfect. Electric charging doesn’t require the same dedicated infrastructure as gasoline—it can happen anywhere there’s electricity. Perhaps that makes our transition more like returning to Bertha’s time, when “refueling” could happen at a pharmacy or any place with the right supplies. Our charging stations might become as invisible as electricity itself, embedded in parking spots, highway pavement, and light poles.

What strikes me most is how each transition begins with people who can see beyond what is to what could be. Bertha Benz didn’t wait for permission or perfect conditions. The Gulf Refining Company didn’t wait for mass automobile adoption before building its station. They helped create the future they envisioned.

As I walked away from those charging stations at EVS Saudi, I wondered what ordinary features of today’s world will become museum pieces tomorrow. And I wondered who among us is the modern Berthas—the ones brave enough to “steal” tomorrow’s technology and show us all what’s possible, even when we’re not quite ready to see it.

Because revolutions don’t announce themselves with trumpets. They begin with quiet acts of courage, with small innovations on lonely roads, with someone willing to stop at a pharmacy and ask for something no one has ever requested before.