Article 4 by Paul Kaman:

“The Electric Refueling Revolution: A 140-Year Love Story with Wings”

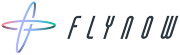

Picture this: it’s a foggy London morning in 1884, and Thomas Parker—the same brilliant engineer who electrified the London Underground—stands beside his latest creation. The carriage before him looks ordinary, except for one revolutionary detail: no horses. No steam. No explosive gasoline engine that could break a man’s arm with a single misplaced crank. Just silence, broken only by the soft hum of electric motors.

Parker doesn’t know it yet, but he’s about to witness the birth of the future. Then lose it. Then, 140 years later, watch it rise again.

This isn’t just a story about cars, charging stations, or refueling stops. It’s a human drama of dreams deferred, fortunes lost and found, and the peculiar way history repeats itself—often with the same cast of characters playing different roles.

Act I: The Golden Dawn (1880s-1920s)

The Unlikely Heroes

The pioneers weren’t who you’d expect. Gustave Trouvé’s 1881 demonstration of a battery-powered tricycle in Paris was met with awe and skepticism. But the real breakthrough came from William Morrison’s electric carriage in the US, which captured America’s imagination in ways no one anticipated.

Here’s the first twist that nobody saw coming: women became the early adopters. Clara Ford, wife of Henry Ford, became a symbol of the modern woman behind the wheel of a Detroit Electric. While men wrestled with dangerous hand-cranked gasoline engines that could break bones, women glided silently through city streets in electric carriages that started with the touch of a button.

The infrastructure was surprisingly sophisticated. By 1900, electric cars accounted for a third of all vehicles on US roads. Battery exchange services and public charging stations began to appear, creating the world’s first electric mobility ecosystem. Imagine pulling up to a charging station in 1905—the attendant would swap your depleted battery for a fresh one in minutes, much like we change phone batteries today.

But here’s where the human drama gets fascinating: The Model T Ford, with its electric starter and low price, became accessible to the masses. Henry Ford’s friendship with Thomas Edison led to partnerships exploring low-cost electric vehicles in 1914. What if that collaboration had succeeded? We might have had mass-market EVs a century ago.

The Great Disappearing Act

Then came the plot twist that changed everything. As road networks expanded and gasoline became cheap and ubiquitous, consumer preference swung decisively toward internal combustion. The economic benefits of mass automobile ownership—job creation in assembly plants, parts manufacturing, and oil refining—shifted toward the gasoline sector.

A gendered stigma began to emerge, with electric cars increasingly marketed as “women’s cars,” a label that would later contribute to their marginalization. What had been a symbol of modernity suddenly became a symbol of limitation.

Act II: The Wilderness Years (1920s-1990s)

Survival in the Shadows

The 1920s and 1930s saw electric vehicles relegated to niche roles—delivery trucks, milk floats, and industrial vehicles. A few manufacturers, like Detroit Electric, survived by serving a loyal but shrinking clientele. These weren’t just business casualties; they were dreams deferred; entire communities whose livelihoods disappeared with the last electric car rolling off the assembly line.

But here’s what most people don’t know: That in factories, warehouses, and urban delivery, electric vehicles continued to prove their worth. The knowledge never truly died—it went underground, preserved by a handful of true believers working in industrial applications, waiting for the world to rediscover what it had lost.

The 1970s brought the first resurrection attempt. The oil crisis and growing environmental awareness sparked renewed curiosity about electric vehicles. The CitiCar, designed by Bob Beaumont, became a symbol of the energy crisis—an affordable, wedge-shaped EV embraced by environmentally conscious consumers.

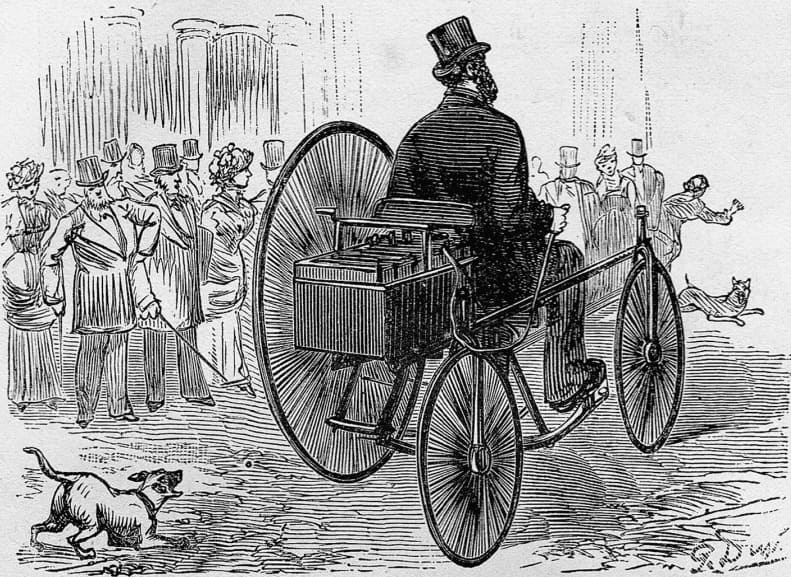

And then something magical happened on the moon. NASA’s electric Lunar Rover, driving on the moon in 1971, captured the world’s imagination. If electric vehicles traverse the lunar surface, surely, they could handle a trip to the grocery store?

Act III: The False Dawn (1990s-2000s)

The Passion and the Betrayal

The 1990s marked a turning point that read like a Shakespearean tragedy. Environmental regulations and the California ZEV mandate forced automakers to develop electric models. Early adopters and environmentalists embraced the GM EV1, Toyota RAV4 EV, and Honda EV Plus.

The betrayal reached a pinnacle when automakers repossessed and destroyed leased EVs, sparking public protests and the documentary “Who Killed the Electric Car?” Picture the scene: passionate drivers chaining themselves to their beloved electric cars, pleading not to have them taken away and crushed. Grassroots advocacy groups like Plug In America emerged, fighting for the right to drive electric.

The drama was palpable. These weren’t just customers losing a product—they were evangelists losing their faith made manifest, communities of early adopters watching their vision of the future destroyed in industrial crushers.

Act IV: The Resurrection (2000s-Present)

The Disruptor’s Gambit

Then came the plot twist nobody saw coming: a startup named after Nikola Tesla, led by a South African entrepreneur who’d made his fortune in internet payments. The founding of Tesla Motors and the launch of the Tesla Roadster in 2008 demonstrated the potential for high-performance, long-range EVs. The Nissan Leaf, launched in 2010, brought affordable, practical EVs to the mass market.

The financial crisis heightened the challenge of building a new industry from scratch. Tesla’s success inspired a new generation of entrepreneurs and forced established automakers to take electrification seriously.

Elon Musk didn’t only build an electric car—he built an entire ecosystem. Tesla’s Supercharger network became the iPhone moment for electric vehicles: suddenly, long-distance electric travel wasn’t just possible, it was preferable.

The Great Acceleration

By 2020, global EV sales surpassed 10 million units, and public charging stations more than doubled in the US. But the real story was happening in communities across America. The US is experiencing a manufacturing renaissance, with over $155 billion in private investment in EV and battery supply chains since 2021.

Urban, affluent communities benefited most from early investments, while rural and disadvantaged areas faced “charging deserts”. Advocates and policymakers worked to ensure that the benefits of electrification were shared broadly.

The Gas Station Parallel: History’s Perfect Mirror

The parallels between gasoline and electric infrastructure are almost mythological in their symmetry. Early gas stations were dangerous, unregulated affairs—attendants hand-pumped fuel into containers, then funneled it into cars. Finding fuel on a long journey was a gamble, standards were nonexistent, and explosions were common enough to make headlines.

The first EV charging stations were basic Level 1 outlets with no standards, unreliable networks, and range anxiety, making any trip beyond city limits an adventure in logistics and prayer.

But here’s what history teaches us: infrastructure evolves from chaos toward standardization and ubiquity. Gas stations transformed from simple pumps into sophisticated multi-fuel dispensers and ultimately convenience ecosystems. The biggest stations today—like Buc-ee’s with its 120 gas pumps and 67,000 square feet of retail space—are destination experiences that happen to sell fuel.

The same evolution is happening with EV charging, but faster. Unlike gasoline, electricity can be delivered almost anywhere. We’re seeing charging stations integrated into shopping centers, workplaces, restaurants, and even streetlights. The infrastructure is becoming invisible, ubiquitous—the way it always should have been.

The Human Stories That Drive Innovation

Behind every technological revolution are individuals whose vision exceeded their era’s limitations. Henry Morris and Pedro Salom built the Electrobat in 1894, completing their project in just two months using a modified ship motor powered by lead-acid batteries. These weren’t just inventors; they were dreamers who saw beyond the immediate constraints of their technology.

Consider Clara Ford again—in an era when women couldn’t vote, she was tooling around Detroit in her electric car, demonstrating a freedom that gasoline cars, with their dangerous hand-cranking, couldn’t provide. Or Thomas Edison, whose belief in electric vehicles was so strong that he partnered with his friend Henry Ford to develop them, even as Ford was perfecting the very gasoline engine that would make electric cars obsolete.

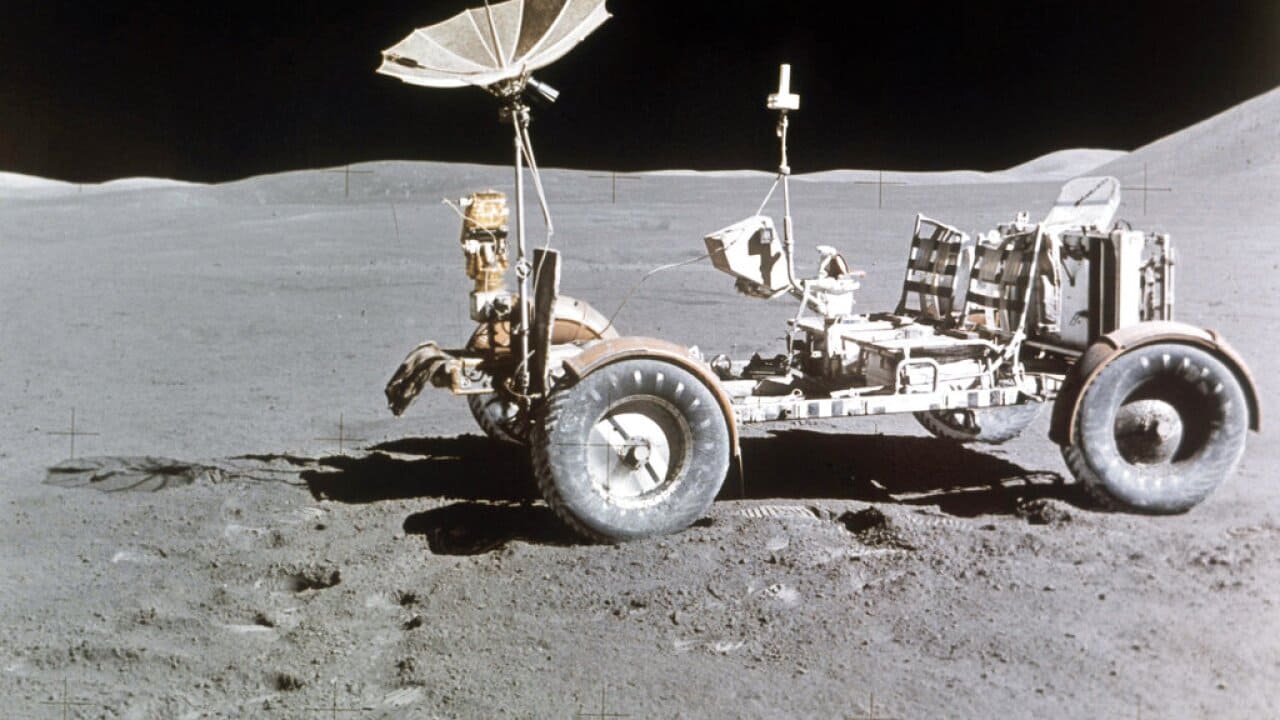

The Henney Kilowatt, produced in 1959–1960, was an early attempt at a modern electric car, though only 47 were built. Each of those 47 cars represents someone who refused to give up on the electric dream during its darkest hour.

The Future: Convergence and the Next Plot Twist

Will EV charging follow gasoline’s path toward massive, multi-purpose destinations? All signs point to yes, but with fascinating variations. The rise of Autonomous Aerial Mobility (AAM) vehicles—essentially flying cars—adds another layer of complexity. These vehicles will likely be electric from the start, requiring three-dimensional charging infrastructure that could be integrated with existing ground-based networks.

Imagine charging stations that serve both your electric car and your air taxi. The technology isn’t science fiction—it’s engineering, and the timeline is shorter than most people think.

The global EV market is projected to reach $8.8 trillion by 2030, reshaping energy markets and creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs. But more than the economics, it’s the human stories that will define this transition.

The Recurring Characters in History’s Play

Here’s the most surprising twist of all: the same types of people who championed electric vehicles in 1900 are championing them today. Environmental advocates, urban professionals, women seeking independence and convenience, engineers obsessed with efficiency, and entrepreneurs willing to bet everything on a cleaner future.

The opponents are familiar too: established industries protecting their investments, politicians worried about job losses in traditional sectors, and consumers skeptical of new technology. Even the arguments are the same—range anxiety in 1910 sounds remarkably similar to range anxiety in 2010.

The situation is heightened by geopolitical tensions, technological disruption, and the urgency of the climate crisis. The surprise is the resilience and adaptability of local populations. Communities in oil and auto regions are finding new paths to prosperity, investing in renewable energy, advanced manufacturing, and digital infrastructure.

The Never-Ending Story

The electrification of transportation isn’t only about technology—it’s about human persistence, the cyclical nature of innovation, and our endless capacity to reimagine mobility. We’re not witnessing the rise of electric vehicles; we’re living through the second act of a story that began 140 years ago, paused for a century-long intermission, and is now accelerating toward a conclusion that would amaze those early pioneers.

The human drama continues, reminding us that progress is not just about technology, but about the people who imagine, build, and live with it every day. From Thomas Parker’s first silent carriage in London to Tesla’s Supercharger networks spanning continents, the story remains fundamentally human: curious, empathetic, full of suspense, and always ready to surprise us.

The next chapter is being written by those who dare to ask new questions, empathize with those left behind, navigate uncertain futures, and embrace the surprises that innovation always brings. The electric revolution, for all its complexity, remains what it has always been—a deeply human enterprise, driven by our hopes, our fears, and our relentless drive to move forward.

In the end, that’s the real parallel between the evolution of gas stations and charging networks: both are expressions of our fundamental human need not just to go places, but to imagine better ways of getting there. And sometimes, if we’re patient enough and stubborn enough, the future we imagined in 1884 finally arrives—140 years later, but right on time.

The Moment Before Everything Changes

Here’s what Thomas Parker couldn’t have imagined as he stood beside his silent carriage in foggy London: that his electric dream would not only return but would become the foundation for humanity’s next great leap. Not just cars. Not just mobility. Something far more revolutionary.

The patterns we’ve traced—the rise, the fall, the resurrection—are about to repeat. But this time, the scale will be different. The impact will be exponential. The possibilities will reshape not just how we move, but how we live, work, and connect as a species.

Think about it: every mobility revolution has been a force multiplier. The railroad didn’t just move people faster—it built nations, created time zones, and sparked industrial empires. The automobile didn’t just replace horses—it birthed suburbs, shopping malls, and entirely new ways of life. Air travel didn’t just shrink distances—it created global commerce, international culture, and made the world feel smaller.

Now imagine if you could combine the electric revolution’s clean efficiency with aviation’s freedom from roads. Imagine if the charging infrastructure we’re building today could serve not just cars, but something that moves in three dimensions. Imagine if the same entrepreneurs, engineers, and dreamers who resurrected electric vehicles are now preparing to give us wings.

The electric vehicle revolution is not a destination—it’s the dress rehearsal. Every charging station, every battery breakthrough, every lesson learned about infrastructure and adoption patterns is preparing us for something that will make the automobile look quaint by comparison. We’re witnessing the final preparation for the most transformative mobility revolution in human history.

The characters are the same. The patterns are identical. The technology is converging. And the timeline? Shorter than you think.

In our final article, we’ll reveal what Clara Ford’s great-granddaughter might be piloting above Detroit’s skyline. We’ll explore how the charging stations being built today will serve vehicles that hardly touch the ground. We’ll discover why every lesson from 140 years of transportation evolution has been preparing us for this singular moment when humanity finally learns to fly, not just as passengers, but as pilots of our three-dimensional future.

The electric revolution was never just about cars. It was about power. Clean power. Distributed power. The kind of power that could lift civilization itself into the air. The kind of convergence that will birth a new economy.

Thomas Parker’s silent carriage wasn’t the beginning of electric vehicles. It was the first whisper of human flight made practical, accessible, and universal. The revolution he started is about to take off—literally.

The age of Advanced Air Mobility is coming. And thanks to everything we’ve learned from the rise, fall, and resurrection of electric vehicles in this article, we’re finally ready for it. From the Homo Sapiens to ‘Homo Ascendens!’