Article 5 by Paul Kaman:

“The Unexpected AAM Catalyst: Why David Triumphs Over Goliath”

During the recent EVS Saudi event in Riyadh, an investor made a statement that left me speechless. “Small Advanced Aerial Mobility (AAM) companies like FlyNow Aviation don’t stand a chance,” he said with absolute certainty.” And specialized firms like Aeroauto Global, who even know what they do? Why would anyone bet on unknowns when you could go with well-funded big-name OEMs?”

His dismissal of agile players like FlyNow and Aeroauto, along with many others, in favor of just a few household names was shocking. Here’s what he overlooked: Aeroauto, a Florida-based company, isn’t an OEM or a part manufacturer; it designs and manages the entire Advanced Air Mobility ecosystem. They offer economic benefits to communities by connecting efficient manufacturers, infrastructure providers, regulators, and government agencies into practical, real-world solutions.

In his worldview, companies like SpaceX or Tesla shouldn’t exist. There was no room for them.

Who here even needs to argue for Elon Musk?

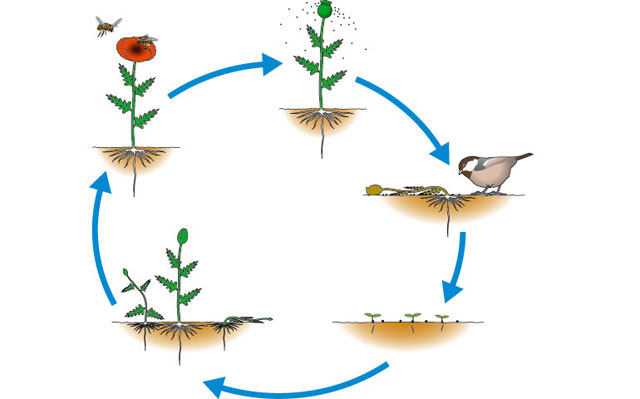

But as I listened to his words, I realized something profound. The investor was asking the seedling to stay small forever, never to challenge the oak’s dominance. However, if we observe nature, it recycles endlessly, relentlessly, and in both directions.

Despite the shock of his words, they revealed something I had been struggling with for years. Many emerging markets have a peculiar psychology where decision-makers prefer established companies, not because they have better technology, but because they appear more credible. It’s safer to fail with well-known names than to succeed with FlyNow or Aeroauto. It’s easier to save face by partnering with household brands than to defend supporting innovative startups that could change everything.

This mindset dominates sectors where officials and investors claim they want to lead but hesitate to support the companies that could make it happen. They speak confidently about becoming AAM leaders, yet when it’s time to act, they seek outside validation and familiar names for reassurance. It’s a self-defeating cycle that stifles innovation while waiting for others’ approval to succeed.

A friend in the region once demonstrated this perfectly. When I recommended yoga breathing exercises that had helped me, he asked earnestly: “Did the US FDA approve yoga?” I nearly fell from my chair. But that GCC investor’s conversation forced me to face an uncomfortable truth: this isn’t really about aviation. It’s about the human tendency to confuse size with inevitability, funding with intelligence, and institutional approval with genuine ability.

So, I did what any curious person would do. I explored history to see if conventional wisdom holds up. What I discovered will surprise you.

The Mathematical Certainty Hidden in Rogers’ Research

Before we explore history’s biggest upsets, let me share something that transforms our understanding of change itself.

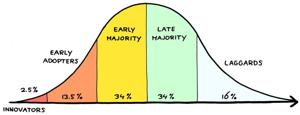

Everett Rogers spent decades studying how innovations spread through society. His Diffusion of Innovation theory reveals a mathematical pattern that explains why that investor’s thinking was not just wrong—it was catastrophically backwards.

Only 2.5% of people are true innovators. Another 13.5% are early adopters. The rest wait. Collectively, these first 16% are your pioneers, your spark, your critical mass.

This is where leadership begins! Not with the crowd, but with the few who believe first.

In my own journey, real change always began the same way: with a small, committed group. Never the majority. We often believe we need everyone on board to start, but that’s not always the case. The tech revolution didn’t start in a boardroom; it began in a garage.

Rogers’ research shows something even more profound: the masses don’t lead innovation—they follow it. That investor was essentially demanding that the 2.5% stop innovating and wait for the 84% to give permission.

It’s like asking fire to wait for wood’s approval before burning.

The Pattern Behind History’s Greatest Upsets

You probably know the story of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, but historians often overlook what happened afterward. Their sacrifice didn’t just slow the Persian advance—it sparked something much more powerful. Scattered Greek city-states, witnessing such bravery, finally united and ultimately defeated the mighty Persian Empire.

It wasn’t their numbers that guaranteed victory. It was a small group of united minds (Rogers’ critical 16%) refusing to accept the impossible.

That same pattern repeats throughout history’s most important moments with mathematical accuracy.

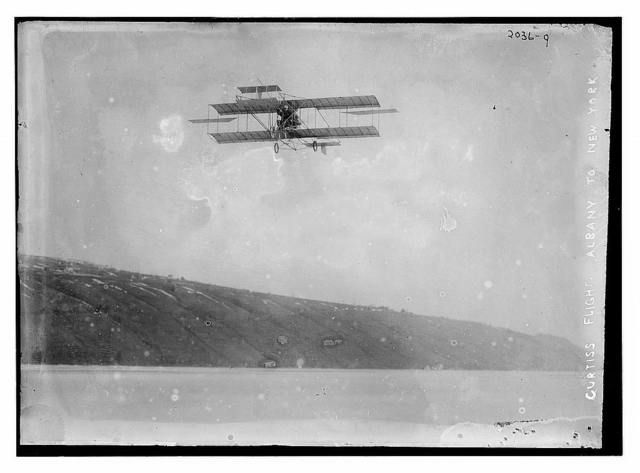

December 1903. The world’s leading experts had declared “heavier-than-air” flight scientifically impossible. Lord Kelvin, Britain’s most renowned physicist, had mathematically proved it wouldn’t work. The Smithsonian Institution had just spent $70,000 (equivalent to $2.5 million today) watching their aircraft take a drink in the Potomac River.

Yet two bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio (whose formal education ended at high school) quietly proved every expert wrong. Wilbur and Orville Wright didn’t just achieve flight; they shattered the scientific establishment’s most confident claims.

They were Rogers’ 2.5%! The true innovators!!

However, here is where the story takes a darker turn, revealing a crucial aspect of institutional resistance. The Smithsonian, humiliated by its failure, refused to acknowledge the Wright brothers’ achievement. Instead, it displayed its own failed aircraft, labeled as “The first man-carrying airplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight.” The institution even enlisted Glenn Curtiss to secretly modify its crashed aircraft, reinforcing original claims while undermining the Wright brothers’ patents.

This institutional sabotage persisted for decades. Only years later did the Smithsonian finally acknowledge the truth and properly honor the Wright Brothers’ achievement. Decades of institutional pride had been prioritized over historical accuracy.

I need to make a personal confession. During my years in Northern Virginia, I had a tradition of taking visitors to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. We would stand quietly before the Wright Flyer, marveling at the courage of those bicycle mechanics who first gave humanity wings. I felt great pride in showcasing these pieces of American aviation history—the pioneering spirit that refused to accept limits.

Learning about the Smithsonian’s disgraceful treatment of the Wright brothers through this research genuinely saddened me. The very institution I trusted to preserve our greatest achievements had spent decades trying to erase them. It’s a powerful reminder that even our most respected institutions can fall prey to petty jealousy and political schemes.

But there’s something even more heartbreaking in this story. The Wright brothers weren’t just battling gravity; they were fighting against the certainty of Rogers’ adoption curve. They understood that 84% of people would resist their innovation until the crucial 16% proved it worked.

They flew anyway.

The Exponential Reality of Corporate Life and Death

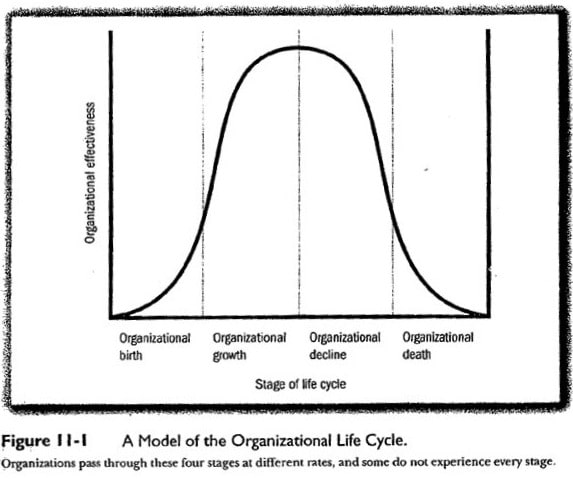

Here’s what that investor couldn’t see, what the Smithsonian refused to acknowledge, and what transforms everything we think we know about business competition.

Nature doesn’t just recycle; it follows an exponential pattern that repeats throughout history with mathematical precision.

- Birth: A new company emerges with remarkable simplicity.

- Growth: It expands quickly, challenging established norms.

- Maturity: It becomes the dominant force.

- Aging: It develops more complexity, bureaucracy, and resistance to change.

- Death: It is replaced by the next wave of disruptors.

This isn’t rebirth—it’s just replacement. And the math doesn’t lie.

The phrase “You can’t replant an old tree” accurately describes the corporate world. Traditional aerospace OEMs, as well as newer ones that haven’t learned these lessons, can’t grow beyond their current limits. They have gathered too much complexity, too many legacy systems, and too many reasons why simple solutions are impossible.

This isn’t a character flaw; it’s a biological necessity. The old oak must die for the forest to renew itself.

The Modern Echo: When Giants Overlook the Obvious

Steve Jobs didn’t come from IBM’s boardroom. Reed Hastings wasn’t found in Blockbuster’s corporate structure. They were Rogers’ innovators, beginning in garages and spare rooms while giants slept.

In 2000, Netflix proposed selling its entire company to Blockbuster for $50 million to avoid increasing legal and financial issues. Blockbuster, which operated 9,000 stores and made $6 billion in revenue, dismissed the offer as “ridiculous.” Their executives couldn’t understand why anyone would want DVDs mailed to them when they could drive to a store to pick them up.

Ten years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy while Netflix transformed the way Americans consume entertainment. The giant that once ruled every American strip mall couldn’t adapt to a simple truth: convenience beats tradition.

I experienced that transition myself. One Friday night in the early 2000s, I waited over ten minutes at Blockbuster, watching families argue over the last copy of the week’s hottest movie. Late fees. Limited selection. The shame of returning movies days overdue—it was a flawed system that felt normal only because it was all we knew.

Then Netflix arrived. No lines. No late fees. Movies are delivered reliably to my mailbox. Within months, my visits to Blockbuster dropped to zero. Yet even while enjoying the convenience, I wondered: how did a company with nearly 10,000 stores and millions of loyal customers miss something so obvious?

The answer was simpler than expected. They weren’t paying attention to what customers wanted—they were defending what they already had. They had become the old oak, too stiff to bend, too rigid to change.

The Airline that Reflects Another David

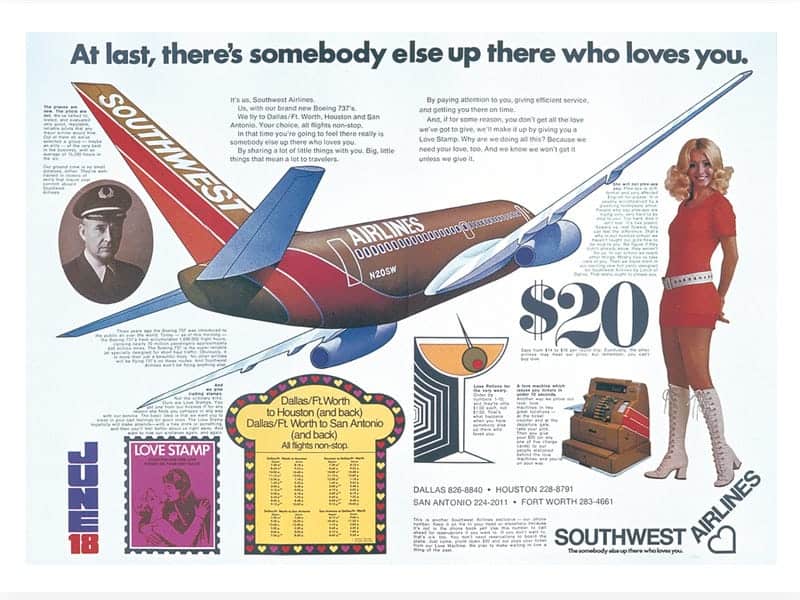

Dallas, Texas – 1971

Herb Kelleher looked over the legal papers spread across his desk. Four years of courtroom battles. Four years of America’s biggest airlines trying to crush his small company before it could carry its first passenger.

Sound familiar?

The powerful carriers had armies of lawyers, billions of dollars in assets, and political ties that reached the highest levels of the American government. They saw Southwest Airlines the way Goliath might have seen that shepherd boy approaching with only a slingshot.

Amusing. Insignificant. Soon forgotten.

But here’s what the giants missed, just like Goliath did three thousand years ago in that valley: sometimes the most dangerous opponent is the one everyone underestimates.

Southwest understood Rogers’s math instinctively. They didn’t need to persuade everyone—only the essential 16% willing to try something different.

The Slingshot Strategy

Legacy carriers were building empires on complexity (hub-and-spoke networks routing passengers through fortress cities, multiple aircraft types requiring specialized maintenance, and first-class cabins whispering “exclusivity).” Southwest was creating something revolutionary with its simplicity:

One plane type. Point-to-point routes. No assigned seats. No meals.

The industry chuckled. “Passengers want amenities,” they insisted.” They demand the full-service experience,” they said.

They were about to discover how profoundly wrong they were.

The Battle Begins

June 18, 1971. Southwest’s first flight took off from Dallas Love Field.

This wasn’t just about moving people from one point to another. It was about something much deeper: democratization – opening up the skies to everyone.

Let’s Step Back a Bit

Before Southwest, flying was mostly reserved for the wealthy, the business elite, and the occasional family taking once-in-a-lifetime trips. A flight from Dallas to Houston costs more than what many people earn in a week. The airlines preferred it that way: fewer passengers, higher profits, and an exclusive clientele.

Southwest envisioned something different. They aimed to compete with Greyhound, not United Airlines. They wanted the secretary, the construction worker, the grandmother visiting family to think: “I can afford to fly.”

They targeted Rogers’ early adopters—people willing to try new things if they provided genuine value.

The established carriers watched Southwest’s early success with increasing unease. This wasn’t supposed to happen. Low cost meant low quality. Customers would see through the gimmick and go back to “real” airlines.

Right?

The Plot Twist that Changed Everything

Here’s where the story makes an unexpected turn—one that clearly demonstrates Rogers’ exponential adoption curve in action.

Southwest didn’t just survive. They didn’t merely grow. They redefined an entire industry’s rules.

By 1990, while legacy carriers hemorrhaged money, filed bankruptcies, and laid off thousands, Southwest remained profitable every single year. Not most years. Every gosh darn single year.

By 2000, their market capitalization had surpassed that of all other major US airlines combined. The shepherd boy hadn’t just beaten Goliath—he’d become the new giant.

But here’s the twist within the twist: Southwest never forgot they were David. They understood that success comes not from converting the masses, but from serving the pioneers who believe before others do.

The Deeper Truth

Southwest’s strength wasn’t in its operational innovations, as impressive as they were. It lay in something more basic: they knew that every customer had been David at some moment.

Baggage fees nickel-and-dime every passenger. Every family believed vacations were financially out of reach, and limited, costly options trapped every business traveler.

Southwest positioned itself as the champion of these everyday Davids, fighting an industry that had become too complacent, too arrogant, and too disconnected from the people it served.

Legacy carriers made Goliath’s mistake: they focused on their strengths instead of understanding their opponent. They saw Southwest’s low prices and assumed it was because of corner-cutting. They observed casual service and thought it was unprofessional. They saw the simple business model and believed it couldn’t scale.

They never saw the slingshot coming.

Victory!

Southwest eventually transported more domestic passengers than any other US airline. They compelled every primary carrier to establish low-cost subsidiaries or adjust their pricing strategies. They trained an entire generation of travelers to expect transparent pricing, friendly service, and accessible air travel.

The David and Goliath story resonates through the ages because it reflects a core human truth: innovation and perseverance can defeat even the strongest giants. But Southwest’s story teaches a vital modern lesson:

The most powerful slingshot isn’t a weapon—it’s understanding what people truly need, then having the courage to build it differently from everyone else.

In the Valley of Elah, David’s victory lasted only a day. In America, Southwest’s success has lasted over fifty years.

The revolution continues to soar, with countless clones around the world. However, the competition has now caught up. Has the former David become today’s Goliath?

Nature’s Exponential Recycling in AAM

What we’re observing in AAM is nature’s recycling process accelerating rapidly. The industry currently invests billions in complex designs that often don’t succeed, caught in what many call the “Wheel of Misfortune.” Meanwhile, something remarkable is emerging at the edges.

- Birth Phase: Companies like FlyNow emerge with radical simplicity.

- Growth Phase: They tap into manufacturing DNA from automotive suppliers.

- Ecosystem Phase: Platforms like Aeroauto and SALAAM.earth deliver integrated solutions.

- Replacement Phase: Traditionally bound OEMs adapt or cease to exist.

The exponent in the growth equation shifts swiftly:

- From negative (skepticism, institutional resistance)

- To positive (proven technology, economic advantages)

- To exponential (mass production, network effects)

- Back to negative (for those who refuse to adapt)

FlyNow Aviation, Aeroauto Global, and the Sky Alliance for Automated Air Mobility (SALAAM.earth) aren’t trying to beat anyone at their own game. They’re entirely changing the rules, acting as force multipliers for Rogers’ critical 16%.

Margaret Mead observed that transformative change rarely comes from large institutions but from “small groups of thoughtful, committed individuals.” She was describing what anthropologists call the “cultural catalyst effect”—how focused passion can reshape entire systems. She was illustrating Rogers’ innovators and early adopters in action.

The ancient Romans understood this when building their extensive road networks. They didn’t start with grand imperial highways. Instead, they began with narrow paths that proved so effective that trade routes naturally followed. Within decades, “all roads led to Rome” not through central planning, but because original designs were so fundamentally sound that expansion became inevitable.

They had captured their critical 16%. The rest followed exponentially.

The Revelation that Redefines Everything

While many remain stuck in old ways, wasting resources on ideas limited by outdated beliefs, FlyNow tackles challenges like those faced by ancient Greek mathematicians, who used geometry to solve revolutionary problems. Instead of accepting inherited limits, they ask: “What if we start from first principles?”

FlyNow’s affordable, efficient, purpose-built eCopter design not only enhances existing concepts but also avoids the fundamental complexity trap that ensnares competitors. Compare this to over $7 billion invested in other programs. Most are delayed, over budget, or have failed to meet expectations.

Meanwhile, FlyNow’s eCopter family, which includes a single-seat, two-passenger, and cargo version, represents a true breakthrough in Urban Aerial Mobility (UAM).

- Development costs: Ten times lower than competitors

- Time to market: Significantly shorter through reduced complexity and a clear path to certification under well-defined regulations

- Performance: 50km range with 25km reserve, 90% lower operating costs

The key insight: FlyNow costs ten times less, not because it’s incrementally more efficient, but because it leverages automotive manufacturing supplier DNA that aviation has never mastered. The time to market is inversely proportional to complexity, as simple solutions scale exponentially faster.

This isn’t a minor improvement. It’s a complete paradigm shift. It’s the seedling that will replace the oak.

Just as Greek city-states learned they could outmaneuver vast empires through coordination rather than confrontation, Aeroauto serves as an ecosystem orchestrator, designing comprehensive AAM integration for economic benefit through multi-modal connectivity. SALAAM.earth builds open ecosystems where different air vehicles operate seamlessly together.

The Alliance is the New Ecosystem

SALAAM.earth (Sky Alliance for Automated Air Mobility) represents something unprecedented, but it’s not a collaboration between old and new. It’s the emergence of an entirely new ecosystem where:

- Different air vehicles operate seamlessly together

- Ground transportation integrates with aerial mobility

- Infrastructure components connect through open standards

- Municipal officials choose integrated solutions over legacy approaches

This isn’t David slaying Goliath—it’s the birth of a new species that makes both David and Goliath obsolete.

The Mathematical Certainty Between Paradigms

Rogers’ research reveals something profound about the moment we’re living through. We’re not in a competition between old and new. We’re in a replacement cycle.

By 2026, a municipal or city official won’t choose between FlyNow and incumbents. They’ll decide between:

- Old paradigm: Complex, expensive, limited-scale solutions from traditional aerospace

- New paradigm: Simple, affordable, mass-produced mobility from automotive-aerospace hybrids

The resident who previously drove two hours to reach medical care will either:

- Keep driving (old mindset continues)

- Fly in 20 minutes for the same price (new approach wins)

There’s no middle ground. It’s a replacement, not a competition.

The exponential curve is unforgiving. It starts slowly, almost invisibly. Then it accelerates beyond anyone’s ability to stop it. Ask Blockbuster. Ask Kodak. Ask any oak tree that ever tried to stop a forest fire.

The Moment of Decision

We stand at our own moment of December 1903. FlyNow Aviation, Aeroauto Global, and SALAAM.earth aren’t asking the aviation industry, government agencies, and investors for permission—they’re inviting them to join Rogers’ critical 16%.

The infrastructure for automated air mobility isn’t just about technology—it’s about reimagining three-dimensional navigation and a new way of life. This requires collaboration between pioneers and the few established players brave enough to embrace exponential change.

To the aerospace industry: Your global reach could accelerate this revolution from decades to years. But only if you’re willing to be part of the 16%, not the 84%.

To government agencies: Your regulatory frameworks and infrastructure investments can ensure this transformation benefits everyone, not just early adopters. You can choose to lead the wave or be swept away by it.

To investors and institutions: Your resources could be leveraged to expand proven innovations instead of funding another spin on the “Wheel of Misfortune.” You can bet on the seedlings or keep watering dead oaks.

The invitation is clear: Join the alliance democratizing the skies, rather than defending patterns that keep us grounded.

Because the only thing more potent than Rogers’ small group of dedicated innovators is when institutions dare to join them before the masses realize what’s happening.

And that moment? It’s happening right now.

The 2.5% have already started. The 13.5% are beginning to take notice. The question isn’t whether the revolution will happen—Rogers’ mathematics guarantees it will.

The question is whether you’ll be part of the 16% who lead it, or the 84% who follow it.

Choose wisely. The exponential curve waits for no one.